Thomas Mann – wat een leven

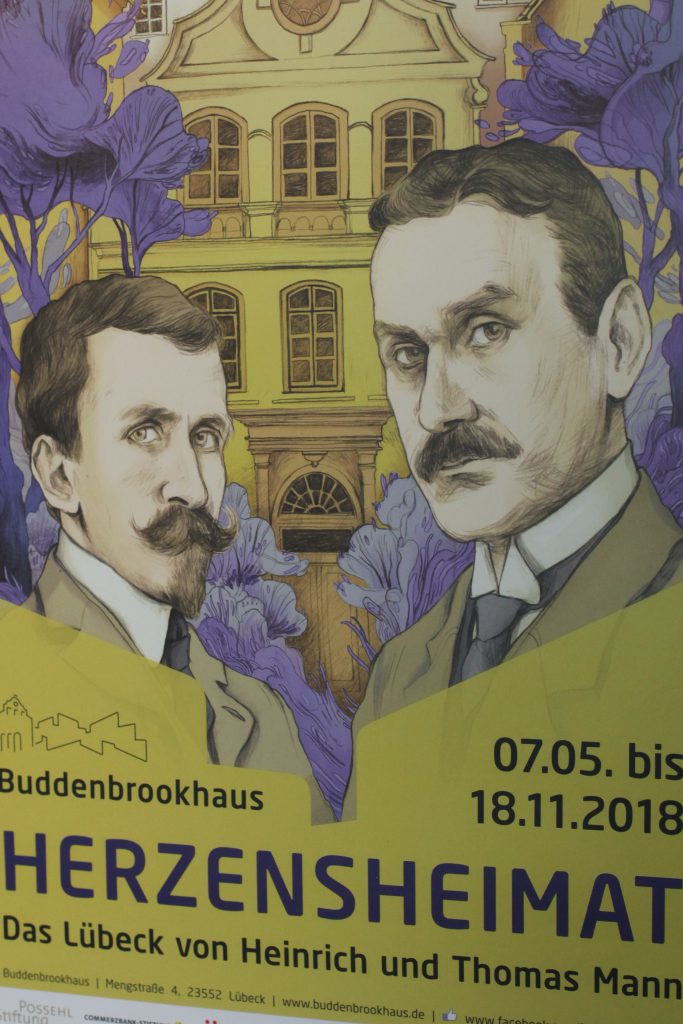

Het moest er ooit van komen. Vijftien jaar geleden bracht ik de lente door met het afronden van mijn masterscriptie over ‘De Toverberg’ van Thomas Mann. Dit voorjaar bezoek ik Lübeck, de geboortestad van mijn literaire held en het decor van zijn debuut ‘De Buddenbrooks’. Uit nostalgie herlees ik voor vertrek nog even de biografische schets van Mann waarmee ik mijn thesis opende. Tijdens het lezen, denk ik: ‘Wat een dramatisch leven had die Mann toch.’ En ook wel: ‘Heb ik dit geschreven? God, wat vergeet een mens veel op vijftien jaar tijd.’ Vandaag dus een vintage tekst op de blog, aangevuld met kersvers beeld van de historische foto’s on display in het Buddenbrooks Haus in Lübeck.

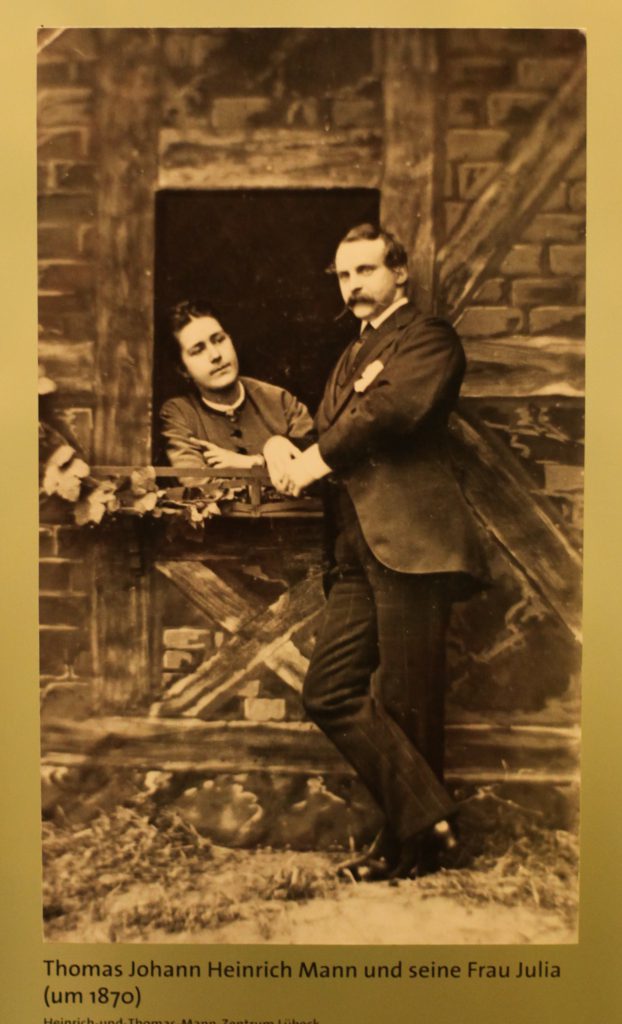

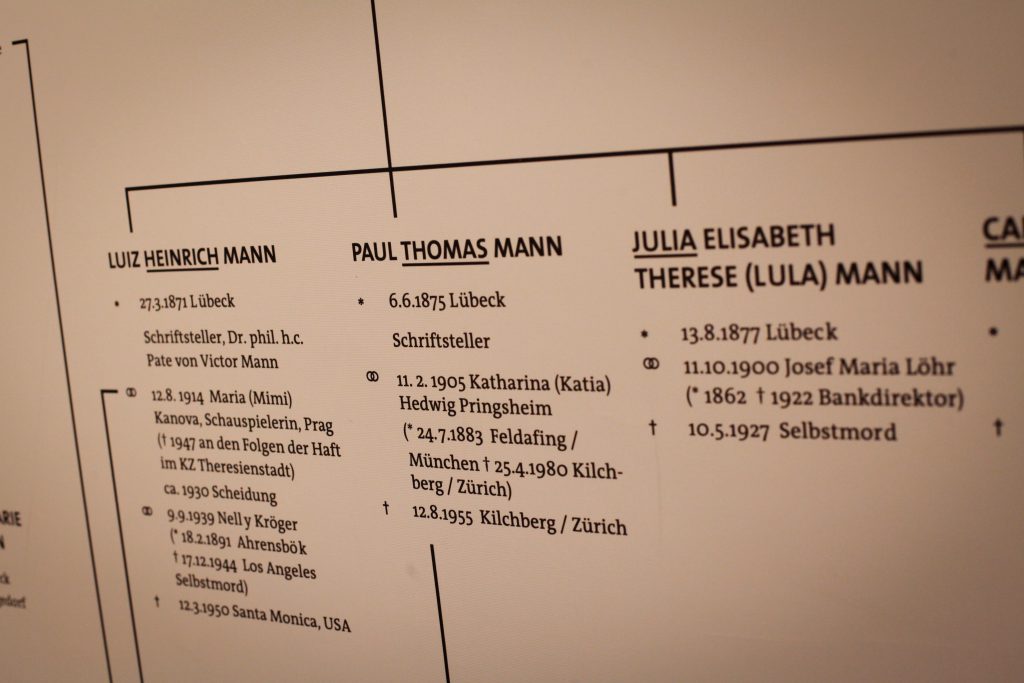

Paul Thomas Mann werd op 6 juni 1875 geboren als de tweede zoon van de welstellende graanhandelaar Thomas Johann Heinrich Mann en de exotische Julia da Silva-Bruhns. Manns vader bezat een graanfirma, was de koninklijke consul van Nederland en werd senator in de hanzestad Lübeck, waar hij met zijn gezin woonde. Thomas, zijn oudere broer Heinrich (°1871), zijn jongere zusjes Julia (°1877) en Carla (°1881) en het nakomertje Viktor (°1890) waren zich bewust van hun sociale status en hadden een natuurlijke air van zelfzekerheid over zich. Hun vader bracht hen de protestantse waarden ijver, vlijt, discipline en zelfbeheersing bij. Hun moeder legde andere accenten in de opvoeding.

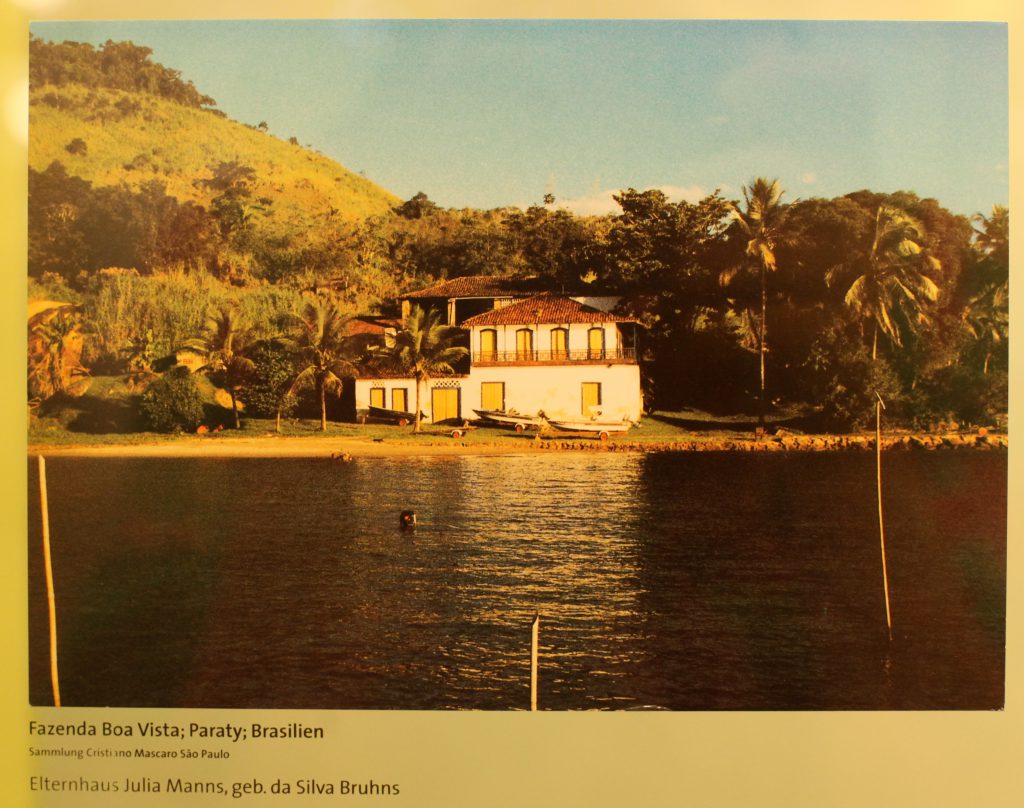

Julia Mann da Silva-Bruhns was geboren in Zuid-Amerika, als dochter van een Duitse plantage-eigenaar en een Portugees-Creoolse vrouw en had tot haar zevende in Brazilië gewoond.

Aan deze periode had ze een exotisch accent en een arsenaal verhalen overgehouden waarmee ze haar kinderen urenlang kon boeien. Ze verwende hen met mooi speelgoed en zong liederen aan de piano om hun gevoeligheid voor kunst te stimuleren. De kleine Thomas erfde evenveel trekken van zijn vader als van zijn moeder en zou opgroeien tot burger én kunstenaar.

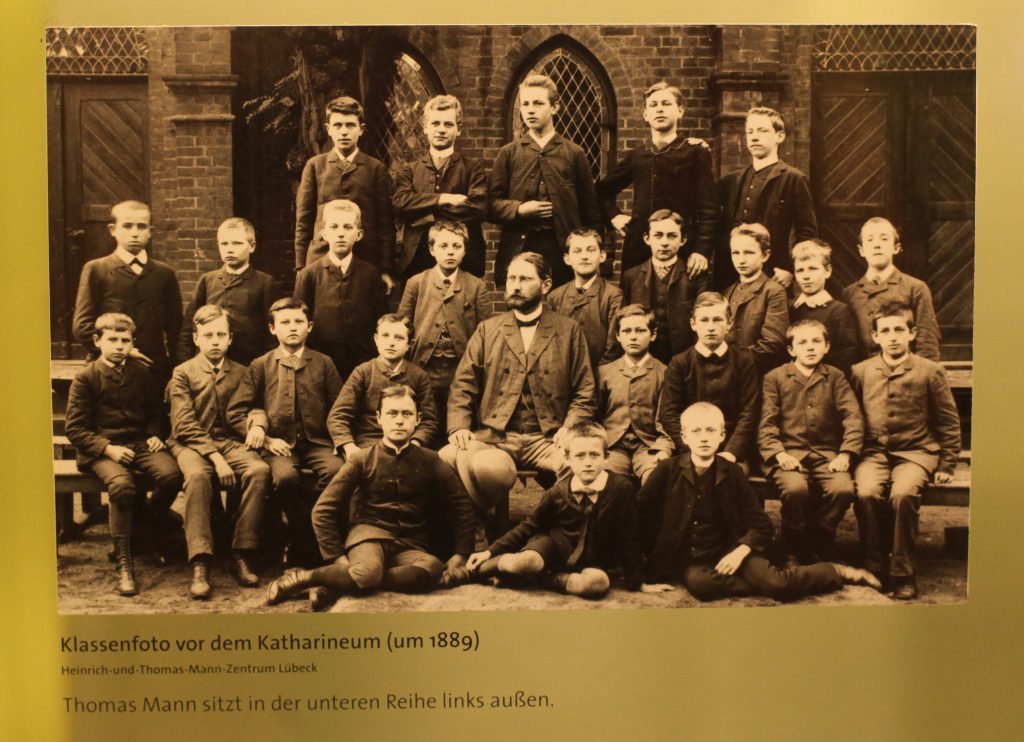

Als jonge student was Thomas Mann niet bepaald een hoogvlieger.

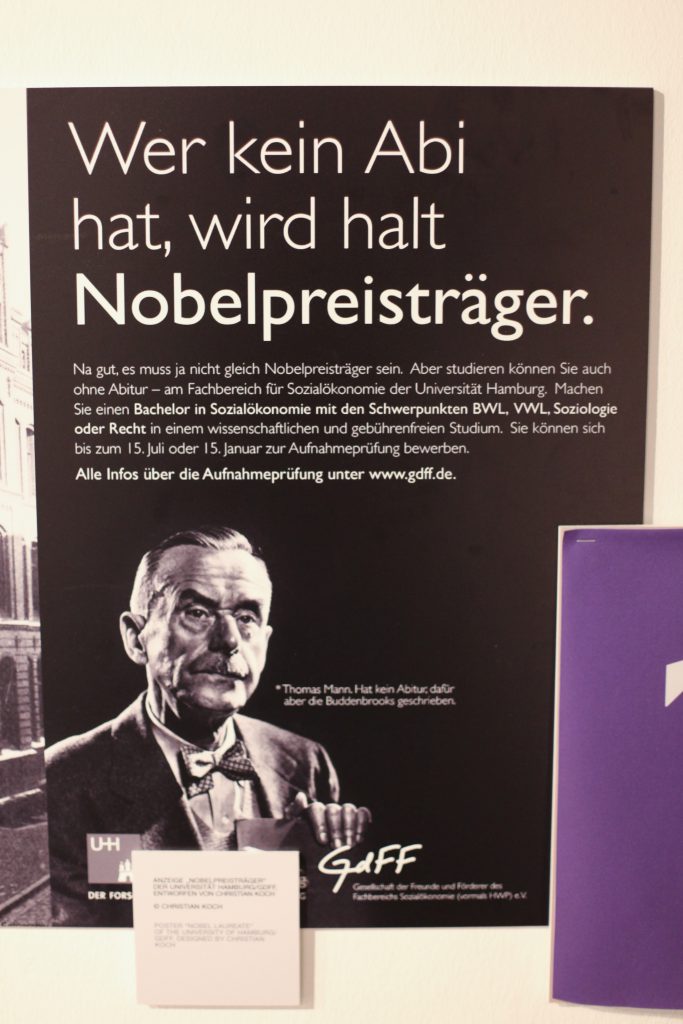

Hij had een hekel aan de Pruisische tucht van het Katharineum in Lübeck –aan de jaarlijkse toneelopvoeringen nam hij wel met geestdrift deel-, en moest maar liefst drie keer zittenblijven. In 1891 overleed senator Mann. Thomas was aanwezig aan het doodsbed van zijn vader en was diep onder de indruk van het serene tafereel. De familiale graanhandel werd verkocht, zoals in het testament werd bepaald, en de oudste zonen erfden een aanzienlijk bedrag. Heinrich verliet Lübeck onmiddellijk en begon aan een nomadenbestaan dat hem naar de Europese hoofdsteden en een aantal Italiaanse sanatoria bracht. Ondertussen schreef hij novellen en verhalen. Thomas bleef aanvankelijk in zijn vaderstad om zijn gymnasium af te maken, tot hij die plannen liet varen en in 1893 zijn moeder, jongere zusjes en broertje vervoegde in hun nieuwe woonst in München. Eindexamen had hij niet afgelegd.

In München werkte Thomas bij een verzekeringsmaatschappij. Hij beperkte zijn sociale contacten om ’s avonds aan zijn novelle “Gefallen” te kunnen schrijven. Die verscheen in 1894 in een bekend literair tijdschrift, dat eerder al twee gedichten van hem had gepubliceerd, onder het pseudoniem Paul Thomas.[1] Hierna volgden een tweede novelle en een aantal essays en recensies die werden opgenomen in het tijdschrift “Das 20. Jahrhundert”, dat door Heinrich werd uitgegeven.

Van deze eerste literaire pogingen nam Mann later bewust afstand.[2]

In 1896 reisde hij met het geld dat hem werd betaald voor de publicatie van de novellen “Der Wille zum Glück” en “Der kleine Herr Friedemann” naar Rome, waar zijn oudere broer op dat moment woonde. Hij trok in bij Heinrich en ontving tot zijn eigen verbazing een brief van de beroemde Berlijnse uitgever Samuel Fischer[3], met de vraag hem een roman toe te sturen.

Zo begon Thomas Mann in Rome op éénentwintigjarige leeftijd aan de roman die hem in één klap beroemd zou maken : “Die Buddenbrooks”. De lijvige roman vertelt het verhaal van vier generaties uit de Lübeckse koopmansfamilie Buddenbrook. Overgrootvader Johann is koopman, grootvader Jean consul en vader Thomas senator. In de loop der jaren stagneert de groei van de familiale graanhandel en begint het maatschappelijke aanzien van de Buddenbrooks te tanen. Hanno, de laatste telg van het patriciërsgeslacht, is een kunstenaarsziel, die de kracht mist om zijn scheppende dromen in daden om te zetten en als adolescent sterft aan tbc.

De ondertitel “Verfall einer Familie” is veelzeggend, en de autobiografische bodem voor het boek is makkelijk achterhaald.

Omdat het een vermomde familiegeschiedenis was, riep Thomas bij het schrijven de hulp in van zijn moeder en zus, die hem brieven vol stambomen, levensbeschrijvingen en recepten toestuurden. Ook de discussies over de familiale verhaalstof die hij in de Italiaanse éénkamerwoning met Heinrich voerde, waren vruchtbaar.[4]

Toen Thomas Mann in 1898 naar München terugkeerde, was het manuscript van “Die Buddenbrooks” ongeveer tot de helft van z’n uiteindelijke omvang gevorderd. Hij ging aan de slag als lektor bij het tijdschrift “Simplicissimus” en werd –bepaald niet tot zijn spijt- afgekeurd voor legerdienst. In zijn vrije tijd las hij de werken van Nietzsche, Schopenhauer en Tolstoj, drie mannen die hij enorm bewonderde. Daarnaast probeerde hij minstens twee uur per dag te schrijven. De invloed van zijn lectuur op zijn schrijfarbeid is duidelijk: het pessimisme van Schopenhauer zit in de sfeer van “Die Buddenbrooks”, terwijl de panoramische compositie herinnert aan Tolstoj.[5] Met werken, lezen en schrijven waren Manns dagen behoorlijk goed gevuld, voor sociale contacten of verstrooiing bleef weinig tijd over. Hij aanvaardde die ascese als een voorwaarde voor zijn artistieke productie:

“Die Entsagung ist unser Pakt mit der Muse, auf ihr beruht unsere Kraft, unsere Würde, und das Leben ist unser verbotener Garten.” [6]

Toch was hij in deze periode zwaarmoedig, gebukt als hij ging onder zijn hooggespannen ambities. Het onmiddellijke succes van “Die Buddenbrooks” in 1901 maakte in dat opzicht veel goed.

Toch begon met de publicatie van zijn eerste roman geen probleemloze periode. Om te beginnen stokte Manns artistieke productie onder druk van het succes. Op vijfentwintigjarige leeftijd had hij een veelzijdig, rijk en goed gecomponeerd boek afgeleverd, waarin hij een hele brok familie- en stadsgeschiedenis had verwerkt, en de thema’s die hem bezighielden –het conflict tussen burger en kunstenaar, tussen leven en geest- uitvoerig had aangekaart.

Diep in zijn binnenste sluimerde de angst, dat hij ‘zijn’ boek geschreven had, en zich in de toekomst alleen nog maar kon herhalen.

Hij had het gevoel dat hij op zoek moest naar nieuwe verhaalstof en een verbeterde stijl en bestudeerde daarom de geschiedenis van Pruisen[7] en het leven en werk van Goethe. Hij schreef een aantal kleinere werken, waarvan vooral het toneelstuk “Fiorenza”, de novelle “Tristan” en de romans “Tonio Kröger” en “Königliche Hoheit” vermelding verdienen. Verder tilde Mann relatief zwaar aan enkele negatieve reacties op “Die Buddenbrooks”, afkomstig van burgers uit Lübeck die ontevreden waren over de (spottende) manier waarop ze in het boek werden opgevoerd. Zijn excuses heeft hij hen nooit aangeboden. Autobiografische ervaringen en indrukken vervormen, stileren en verheffen tot het niveau van de kunst was in zijn ogen niet alleen een legitiem procédé, het vormde de essentie van zijn schrijverschap en daarvoor wilde hij zich niet verontschuldigen.[8]

Een ervaring uit de periode na “Die Buddenbrooks” die later veelvuldig literair bewerkt zou worden[9] was Manns intense en homoseksuele verliefdheid op de schilder Paul Ehrenberg.[10]

Zijn verhouding met Ehrenberg – een flirterig, drukbezet en oppervlakkig type – bleef platonisch en duurde slechts drie jaar (1900-1903). Desalniettemin kenschetste de schrijver haar als ‘die zentrale Herzenserfahrung meiner 25 Jahre’.[11]

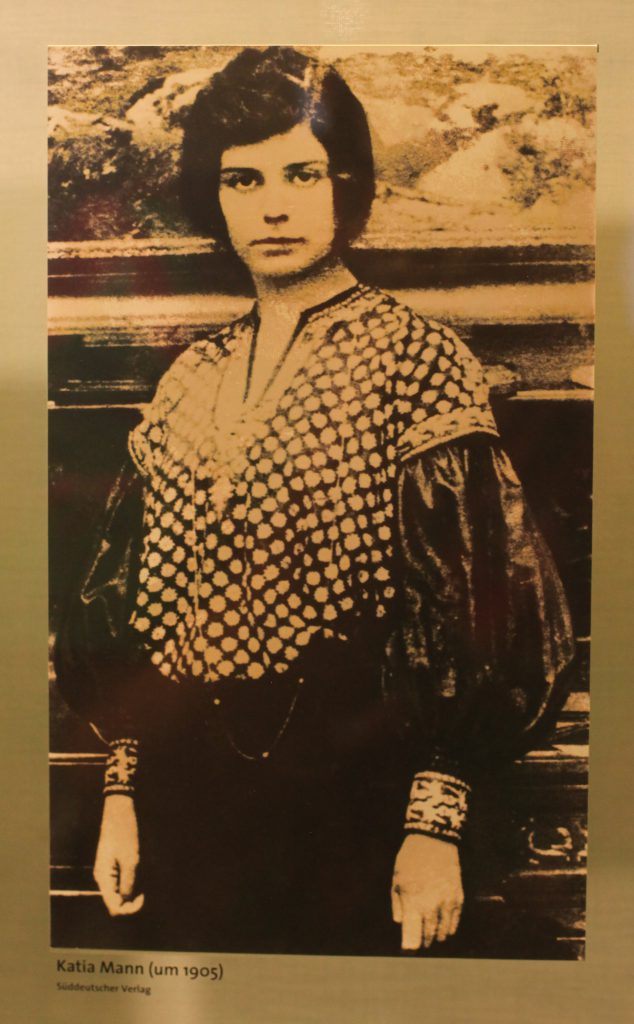

Mann zou voortaan een scherp onderscheid maken tussen homoseksuele liefde, die hij als rein en echt aanzag, en heteroseksuele, die volgens hem steeds in dienst van de geslachtelijkheid stond. Uit angst om gestigmatiseerd te worden verdrong hij zijn homoseksualiteit inzoverre hij zichzelf verbood haar lichamelijk te beleven: hij sublimeerde haar in zijn kunst. Toen hij in 1905 met Katia Pringsheim trouwde, de dochter van een joodse professor in de wiskunde, koos hij definitief voor de warmte en geborgenheid van een door de maatschappij aanvaarde relatie.

Zijn besluit om te huwen werd ingegeven door verstandelijke argumenten: hij voelde zich aangetrokken tot de rijkdom en de cultuur van de familie Pringsheim. Zijn eigen familie was niet opgezet met het huwelijk: zijn exotische moeder vond Katia te koel en te afstandelijk. Heinrich was op het trouwfeest niet eens aanwezig. De spanningen tussen de broers over persoonlijke, morele en literaire zaken hadden zich opgehoopt.[12]

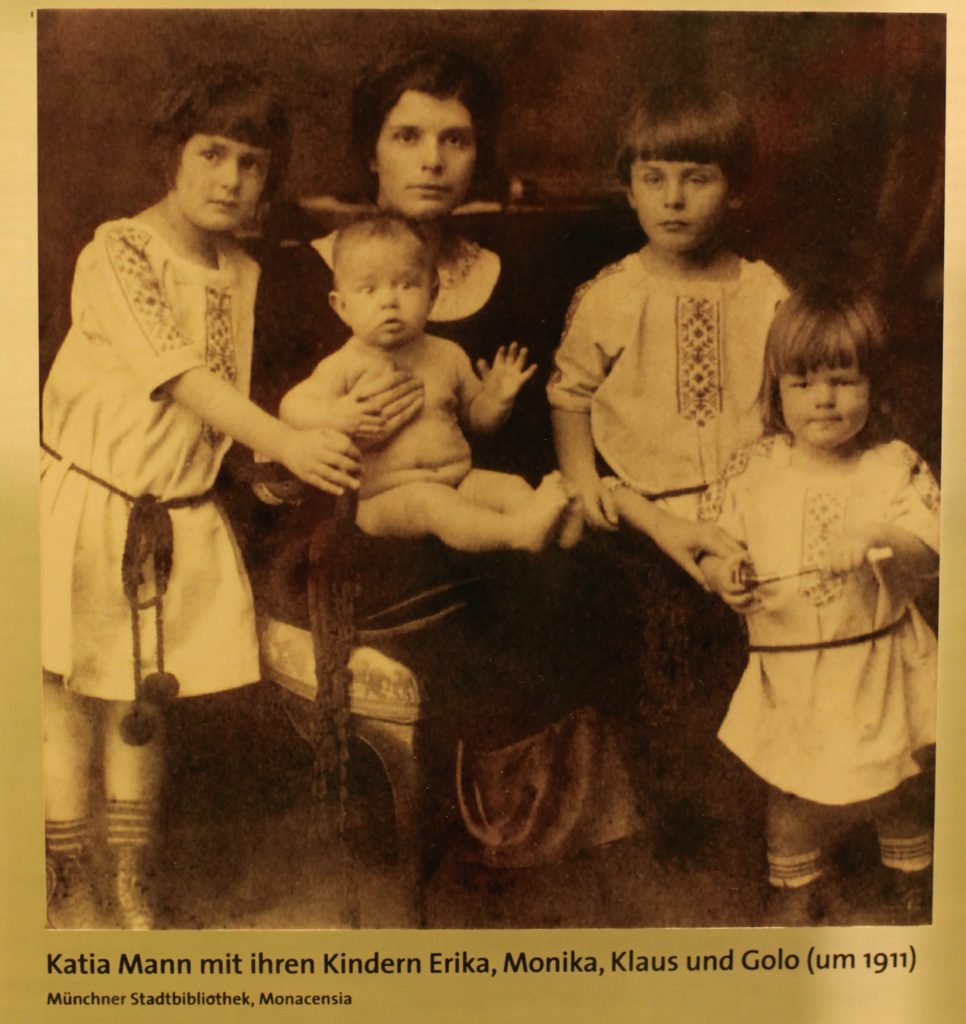

Met zijn huwelijk begon voor Thomas Mann geen uitzonderlijk gelukkige, maar toch een stabiele periode. Op veertien jaar tijd kregen hij en Katia zes kinderen : Erika (°1905) , Klaus (°1906) , Angelus –‘Golo’- (°1909) , Monika (°1910) , Elisabeth (° 1918) en Michael (°1919). Katia leidde het huishouden, al voelde ze zich regelmatig ziek of zwak, en nam de zakelijke kant van Thomas’ carrière op zich, zodat hij zijn aandacht volledig aan het schrijven kon wijden. In het zomerhuis in Bad Tölz (gebouwd in 1908/ verkocht in 1917) beleefde Mann een aantal rustgevende én inspirerende zomers met zijn gezin. Hij raakte bevriend met de componist Gustav Mahler en ontdekte in diens werk een kunstprocédé dat hij zou overnemen: Mahler gebruikte traditionele motieven en beelden, maar herschikte ze tot een toekomstgericht geheel. Hij trachtte de mythologische erfenis niet zozeer te bewaren of reproduceren als wel nieuw leven in te blazen.

Thomas Mann boorde voortaan naast de autobiografische, ook de mythologische inspiratiebron aan.[13]

Zijn artistieke produktie kwam spontaan in een stroomversnelling: in 1912 verscheen de novelle “Der Tod in Venedig” en datzelfde jaar nog begon hij aan “Der Zauberberg”, een boek dat hij concipieerde als een parodie op de sanatoriumwereld, die hij op bezoek bij zijn zieke vrouw in Davos had leren kennen.

In augustus 1914 brak de Eerste Wereldoorlog uit en Thomas Mann begroette hem met onvervalst enthousiasme.[14] Hij verwaarloosde zijn literaire bezigheden ten voordele van een reeks publicaties over de actuele gebeurtenissen en de toestand van Duitsland, waarbij hij zich opstelde als conservatieve nationalist. Zo kwam hij opnieuw in aanvaring met Heinrich, die als pacifist tegen de oorlog was. De politieke onenigheid –bovenop de oude geschillen- veroorzaakte een breuk tussen de broers die zeven jaar zou duren (1915-1922).

In het voorjaar van 1918 – nog tijdens de oorlog – verschenen de “Betrachtungen eines Unpolitischen”, Manns monumentale reflectie op de Duitse geschiedenis en haar apolitieke Kultur.[15] Aan dit document had hij meer dan twee jaar geschreven en het was de synthese van zijn (reactionaire) denken tijdens de oorlogsjaren. Het werk kondigde zichzelf aan als een grote ‘bekentenis’, maar bleef eigenlijk heel rhetorisch:

Mann gaf van zichzelf alleen prijs wat hij prijs wilde geven.

Duitsland verloor de oorlog en kwam in 1918 zwaar geschonden uit de strijd. De Novemberrevolutie, de inflatie en de perikelen in de prille Weimarrepubliek deden Mann vervreemden van zijn standpunten in de “Betrachtungen”.[16] Al in 1923 sprak hij zich tegen het Duitse nationalisme uit. Hij kreeg geleidelijk meer waardering voor de bredere, Europese ‘Zivilisation’ en met die herziening van zijn politieke ideeën werd toenadering tot Heinrich mogelijk.[17] Na de oorlog keerde Manns interesse terug naar de literatuur. Hij schreef essays over Goethe, Tolstoj, Lessing, Nietzsche en Freud[18] en nam ook de draad van “Der Zauberberg” herop. De oorlogsgebeurtenissen hadden zijn visie op het werk wel merkbaar verruimd:

uit de kleine satire op de sanatoriumwereld groeide een omvangrijke, ‘grote’ roman die de mentaliteit van het vooroorlogse Europa schilderde.

Het boek verscheen in 1924 en werd positief ontvangen. Een jaar later vierde Thomas Mann zijn vijftigste verjaardag door een nieuw project op te starten: hij besloot het verhaal van de bijbelse Josef neer te schrijven, die door zijn vader bemind maar door zijn broers benijd werd en het uiteindelijk tot koning van Egypte zou brengen. Om materiaal te verzamelen las hij in de familiebijbel en ging op reis naar Egypte. Het oorspronkelijk kleinschalige plan kreeg –alweer- steeds grotere proporties. Pas achttien jaar en een vierdelige romancyclus later had Mann het gevoel klaar te zijn met de Josef-stof.

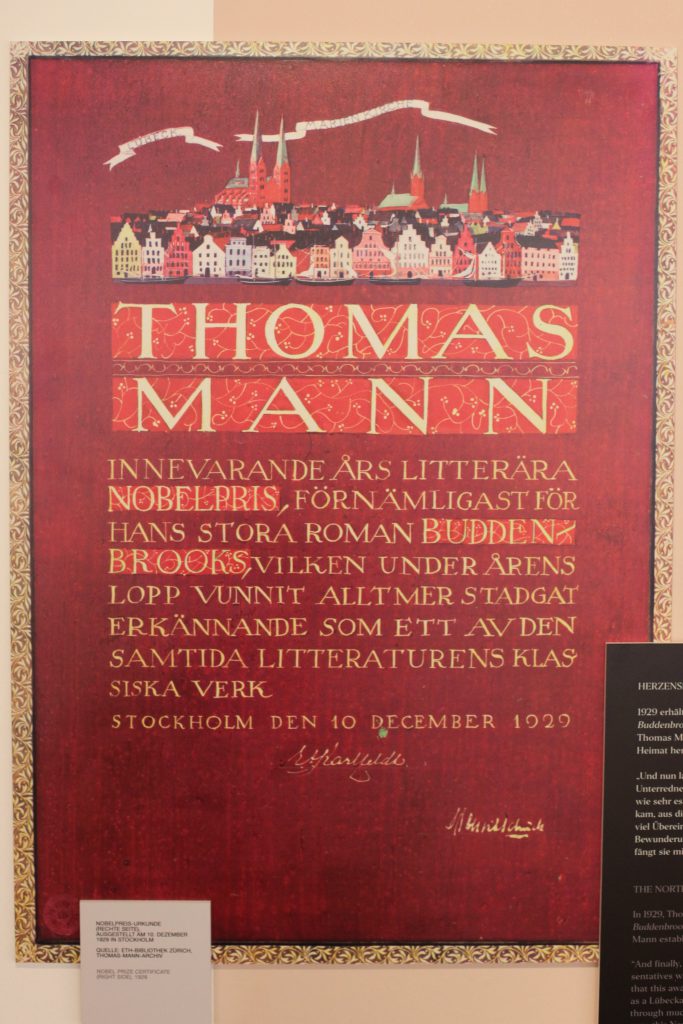

De jaren twintig brachten een aantal persoonlijke verliezen: Manns moeder stierf in 1923, vier jaar later- in 1927- pleegde zijn zus Julia zelfmoord, net als zus Carla in 1911 had gedaan. Professioneel ging het hem echter voor de wind. Het schrijven ging moeiteloos en in 1929 ontving hij de (misschien wel) hoogste onderscheiding die een schrijver te beurt kan vallen: de Nobelprijs.[19] Hiermee bereikte Mann het toppunt van zijn roem en zijn gezin deelde in de belangstelling.

Zijn lievelingskinderen[20] Erika en Klaus waren ondertussen twintigers en ontpopten zich tot kunstenaars. Erika was actrice en cabaretière, Klaus had op negentienjarige leeftijd zijn eerste roman gepubliceerd.

Beiden hielden er een decadente levensstijl op na en de Duitse roddelbladen hadden aan hun spilzucht en schandaaltjes[21] een vette kluif. De kinderen Mann waren een geliefd doelwit voor kritikasters, die zich niet durfden uitspreken tegen hun vader, wiens reputatie in die tijd quasi onaantastbaar was.[22]

Als internationale beroemdheid ondernam Mann een aantal voordrachtsreizen naar de grote Europese steden. Hij ontmoette er literatoren, ministers en consuls en sprak zich in hun bijzijn uit vóór de Duitse toetreding tot de Volkenbond. Na een korte periode van desinteresse, volgde Mann de internationale politiek immers weer op de voet. Hij nam voor het eerst politiek stelling in een literair werk. De in 1929 tijdens een bezoek aan Italië geschreven en in 1930 gepubliceerde novelle “Mario und der Zauberer” was duidelijk anti-fascistisch. In september van dat jaar behaalden de Duitse nationaal-socialisten een onheilspellende verkiezingsoverwinning. Kort daarop hield Thomas Mann in Berlijn een toespraak, waarin hij aan de gezonde redelijkheid van de Duitsers appelleerde en pleitte voor het beteugelen van het fascistische fanatisme. Hij mocht uitspreken, maar moest na afloop langs een zijdeur worden weggeleid en ontving zijn eerste dreigbrieven.[23]

In februari 1933 –een maand na het aantreden van Hitler als Rijkskanselier- ging Thomas Mann op Europese tournee met een omstreden voordracht over Wagner. In de Duitse pers kwam een hetze tegen hem op gang[24] en tegen de zomer was het duidelijk dat het niet veilig zou zijn om naar Duitsland terug te keren.[25] De familie Mann begon haar emigrantenbestaan in een reeks hotels rond de kust van de Middellandse Zee, tot ze zich in oktober in een huis in het Zwitserse Küsnacht neerliet.

In februari 1936 waagde Mann zijn eerste expliciet anti-fascistische stellingname op vreemde bodem, waarna hem prompt het Duitse staatsburgerschap werd ontnomen.

Hij aanvaardde het aangeboden Tsjechische staatsburgerschap maar moest vervolgens lijdzaam toezien, hoe de internationale gemeenschap het in 1938 naliet te reageren op Hitlers inname van Tsjechoslovakije. Tijdens een lezingstournee in de Verenigde Staten rijpte het plan om daarheen te verhuizen. Via Parijs en Bologna trokken Thomas en Katia naar New Jersey, waar Mann professor werd aan de universiteit van Princeton.[26]

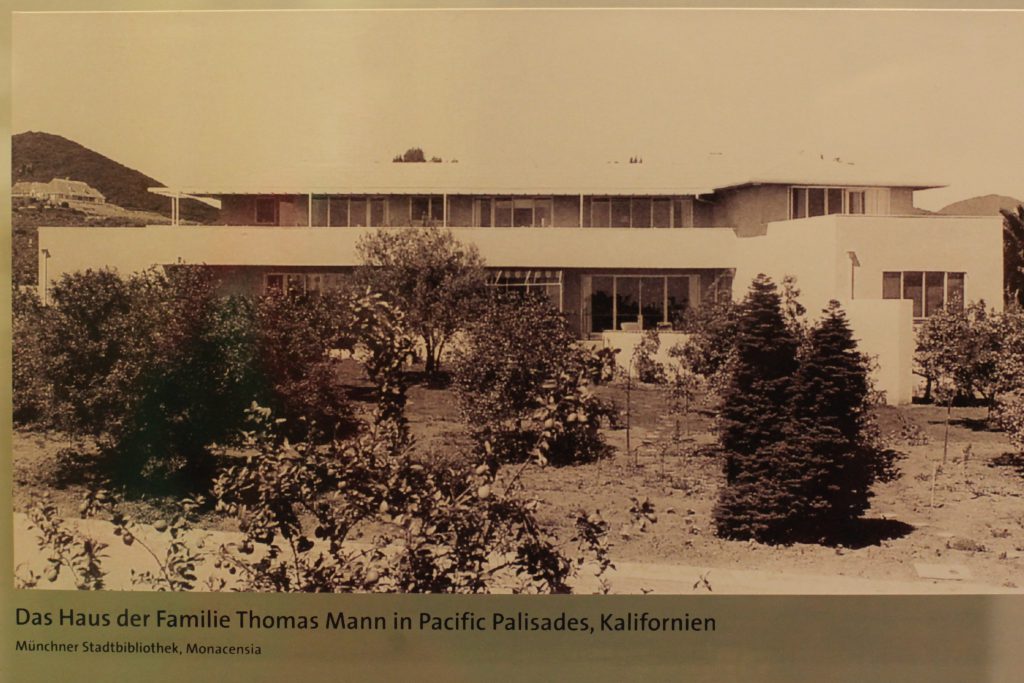

Met de Duitse inval in Polen in 1939 begon de Tweede Wereldoorlog, die Thomas Mann in Amerika zou doorbrengen: tot 1941 in New Jersey, daarna in een villa in Santa Monica, in de staat Californië. Hij voltooide de roman “Lotte in Weimar” (1939), waarin hij zijn liefde voor en kennis van Goethes oeuvre had verwerkt, en de romancyclus “Joseph und seine Brüder” (in 1943). Hij begon zelfs aan een nieuwe roman, “Doktor Faustus” (1943-1947) die het Faustthema en een stuk autobiografie combineerde met een zoektocht naar de wortels van het fascisme. Zijn hart lag in deze politiek woelige tijden nog steeds bij de kunst, al verzaakte hij niet aan zijn ‘plichten’: als figuur met internationale bekendheid vroeg hij de Amerikanen steun voor derden – Duitse emigranten en joodse vluchtelingen- en bedankte alle schenkers met een handgeschreven briefje, hoe klein hun gift ook was geweest.[27] Hij verwierf in 1944 het Amerikaanse staatsburgerschap en trachtte blijk te geven van een onwrikbaar geloof in de democratie, wat soms moeite kostte: zijn afkeer van Hitler was oprecht, zijn enthousiasme voor de democratie voelde soms als een opgedrongen rol.[28]

Officieel eindigde de Tweede Wereldoorlog in 1945, in werkelijkheid ging hij geruisloos over in een nieuw conflict: de Koude Oorlog. Mann keerde niet terug naar Duitsland[29], maar voelde zich ook in het naoorlogse Amerika steeds minder goed thuis.

Hij vernam er in 1949 dat zijn zoon Klaus zelfmoord had gepleegd in Cannes en in 1950 stierf Heinrich, die ook een decennium in Santa Monica had gewoond.

Toen onder president Mc Carthy de klopjacht op alles wat communistisch leek, losbarstte, werd Mann plots een ‘apologist for Stalin’ genoemd. Hij wachtte niet tot hij zou worden verhoord over zijn ‘UnAmerican Activities’, maar keerde Amerika in 1952 gedesillusioneerd de rug toe, om zich weer in Europa, in Zwitserland te vestigen.[30]

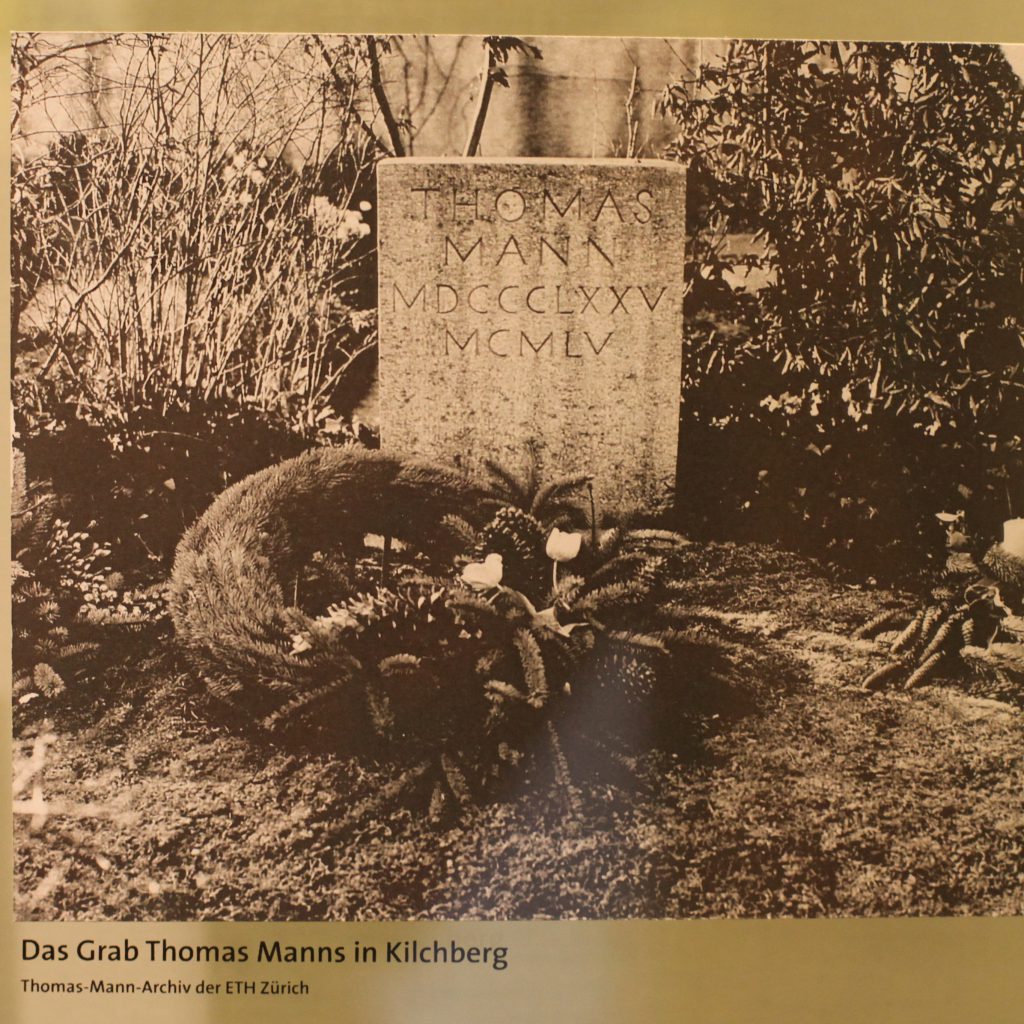

Hoewel Mann ondertussen bijna tachtig jaar oud was, bleef zijn artistieke productie op gang. In 1954 verscheen “Der Erwählte”, een roman geïnspireerd op Hartmann von Aues vertelling “Gregorius”, over een man die na incest met zijn moeder toch paus werd. Zijn laatste werk “Die Bekenntnisse des Hochstaplers Felix Krull”[31] was levendig –tijdens het schrijven beleefde Mann een niet meer verwachte verliefdheid- maar bleef onvoltooid. In 1955 werd hij tot eredoctor van de universiteit van Jena en ereburger van de stad Lübeck verkozen. Laatstgenoemde huldiging ontving hij in de historische zaal van het stadhuis van zijn geboortestad. Hij beschreef de ceremonie als een ‘groots en roerend moment’ in zijn ‘ten ruste neigende leven’[32] en zag er een verzoening in, niet alleen met zijn stad, maar ook met zijn vaderland. Eind juli van dat jaar werd hij geveld door een trombose. Een opname in het ziekenhuis van Zürich kon niet meer baten: op 12 augustus 1955 stierf Thomas Mann aan de gevolgen van arteriosklerose.

[1] De dubbele voornaam van Thomas Mann.

[2] Mann weerde de novelle “Gefallen” uit zijn verzameld werk, omdat hij zich schaamde voor dit onrijpe en onmelodieuze werk. Zijn medewerking aan “Das 20. Jahrhundert” verzweeg hij later maar liever, wegens het nationalistische en anti-semitische karakter van het tijdschrift. Klaus Schröter: Thomas Mann. Rowohlt, Hamburg, 2001. p.34-39.

[3] Fischer had eerder al “Der kleine Herr Friedemann” gepubliceerd en vijf andere novelles van Thomas Mann aanvaard. Schröter (zie noot 2), p.46.

[4] Na de publicatie van “Die Buddenbrooks” staken roddels de kop op, dat het boek het resultaat zou zijn van een literaire samenwerking tussen de broers. De raadgevingen van Heinrich Mann werden mondeling gegeven en dus is de grootte van zijn invloed moeilijk te bepalen. Zelf beweerde hij althans: “Wenn ich mir die Ehre beimessen darf, habe ich an dem berühmten Buch meinen Anteil gehabt; einfach als Sohn desselben Hauses, der auch etwas beitragen konnte zu dem gegebenen Stoff. Das Wesentliche, ihr Zusammenklang, die Richtung wohin die Gesamtheit der Personen sich bewegte – die Idee selbst gehörte dem Autor allein.” Geciteerd in Schröter (zie noot 2) p. 55.

De broederlijke samenwerking in Italië moet men zich niet als overdreven idyllisch voorstellen. Thomas was in deze periode depressief. Heinrich en hij werkten elk aan een eigen boek en hun gesprekken resulteerden niet alleen in kruisbestuiving, maar ook in een concurrentiestrijd. Soms verweet de ene broer de andere bijvoorbeeld dat hij een idee of motief had gestolen. Hermann Kurzke: Thomas Mann. Das Leben als Kunstwerk. Eine Biographie. Verlag C.H. Beck, München, 1999. p.114-118.

[5] Voor de Russische realist Lev Nikolajevitsj Tolstoj (1828-1910) had Thomas Mann veel respect. Rond 1923 prees hij hem als één van zijn twee grote voorbeelden in de redevoering “Goethe und Tolstoi”. Die tekst was het eindpunt van een fascinatie die veel vroeger was begonnen. Een kwarteeuw eerder, ten tijde van het schrijven aan “Die Buddenbrooks”, bestudeerde Mann in het oeuvre van Tolstoj de rijkdom aan concrete details, het gebruik van leitmotive om een literair werk van aanzienlijke omvang samen te houden en het moraliserende aspect. Deze technieken nam hij vervolgens grotendeels over. “Nietzsche und Schopenhauer haben Thomas Manns Einsichten, seine Meinungen bestimmt und gefördert. Tolstoj war das Vorbild seines künstlerischen Schaffens, seines Tuns.” Schröter (zie noot 2), p.63.

[6] Geciteerd in : Ulrich Karthaus : Literaturwissen. Thomas Mann. Philipp Reclam, Stuttgart, 1994. p.20.

[7] Hij speelde met het idee om een boek over Frederik de Grote te schrijven. Zijn voorbereidingen hiervoor werden bij het uitbreken van de Eerste Wereldoorlog als studie uitgegeven.

[8] Dit is een interessante tegenstrijdigheid in Thomas Mann. Enerzijds geloofde hij –zoals boven vermeld- dat een kunstenaar zich als een asceet van het leven moet onthouden om tot artistieke productie te kunnen komen. Alleen wie het leven de rug durft toe te keren, vindt genoeg tijd en concentratie om te scheppen. Anderzijds moet een kunstenaar ervaringen en gevoelens hebben doorleefd, voor hij hen in kunst kan omvormen. Mann lost die tegenstrijdigheid op, door soms bewust ervaringen uit te lokken. “Ich bin Künstler genug, Alles mit mir geschehen zu lassen, denn ich kann Alles gebrauchen.” Geciteerd in Kurzke (zie noot 4), p.152. Tegelijkertijd valt het critici steeds weer op dat meerdere boeken van Mann door dezelfde ervaringen gedragen worden. Hermann Kurzke merkt op: “Die Literatur bietet mehr als das Leben (…) Der eigentliche Erlebniskern ist verhältnismäβig mager gewesen” en “Aus wenig Erlebtem hat Mann viel gemacht.” Ib. p 152 en p. 326.

[9] Het duidelijkst in de novelle “Tonio Kröger” (1903), het kortverhaal “Ein Glück” (1903) en de romans “Joseph in Ägypten” (1936) en “Doktor Faustus” (1947). Kurzke (zie noot 4) p. 133-154.

[10] Deze verliefdheid kwam niet uit de lucht gevallen. Als schooljongen had hij eerder al homoseksuele gevoelens gekoesterd voor Williram Timpe, een jongen van Slavische afkomst. Kurzke (zie noot 4) p. 50-54.

[11] Kurzke (zie noot 4) p. 139.

[12] Na het succes van “Die Buddenbrooks” overschaduwde Thomas’ reputatie die van zijn broer. Terwijl Thomas verstomde onder druk van zijn beroemdheid bleef Heinrichs literaire produktie overvloedig. Heinrich ging daarenboven om met prostituées, hetgeen Thomas moreel verwerpelijk vond. Op zijn beurt bekritiseerde Heinrich het berekende huwelijk met Katia Pringsheim. Volgens Thomas was de échte (homoseksuele) liefde zuiver en platonisch, volgens Heinrich bestond er niets anders dan de zinnelijke (heteroseksuele) liefde. In zijn boek “Die Jagd nach Liebe” – een immorele vertelling over geld, driften en brutaliteit- tekende hij een wereldbeeld dat voor Thomas zo bedreigend was, dat hij het boek wel moest neersabelen. De literaire stijl van de broers verschilde ook aanzienlijk. Heinrich was een grootmeester in het satirische en groteske genre. Thomas schreef in een ironische, maar realistische stijl. Elkaar waarderen betekende de eigen esthetische waarden in vraag stellen: elkaar bekritiseren was de gemakkelijkere optie. Dat ze elkaar onder vuur namen, wilde overigens niet zeggen dat ze kritiek van derden duldden. Tegenover de buitenwereld verdedigden Thomas en Heinrich Mann elkaar haast altijd. Kurzke (zie noot 4), p. 114-130.

[13] Karthaus (zie noot 6) p. 76-77. Concreet zou Mann bijbelse verhaalstof bewerken in zijn “Joseph”-cyclus (1933-1943) en het Faustmotief herscheppen in “Doktor Faustus” (1947).

[14] Enerzijds zag hij in de oorlog de terugkeer van verdrongen krachten: na jaren van materiële en sociale verwennerij, waarin arbeid als de hoogste levensinvulling had gegolden, stelde de maatschappij zich in 1914 plots weer de vraag naar de bovenpersoonlijke zin van individuele inspanningen. Daarom begroette hij de oorlog als een positieve, ‘sinnstiftende’ kracht. Kurzke, (zie noot 4), p.260. Anderzijds geloofde hij dat Duitsland en zijn ‘Kultur’ (nationaal, apolitiek) een bijzondere plaats innamen binnen de westerse ‘Zivilisation’ (westers, democratisch). Om de ziel van het Duitse Keizerrijk te behoeden voor afvlakking door westerse, democratische krachten was de oorlog onvermijdelijk. Schröter (zie noot 2), p.90. Mann voelde ook een zekere opwinding omdat hij getuige ‘mocht’ zijn van zo’n belangrijke wereldgebeurtenissen. Kurzke (zie noot 4), p.241.

[15] Duitsland was pas in 1871 en dan nog op militaire wijze ééngemaakt. Het grootste deel van de negentiende eeuw had het land bestaan uit een verzameling totalitaire, op absolutistische leest geschoeide kleine vorstendommen. Duitsland had daardoor een aantal democratische ontwikkelingen gemist.

[16] Martin Walser erkent dat Mann poogde om zijn politieke denken te herbronnen na de oorlog, maar vindt dat het hem eigenlijk niet gelukt is. “In den Aufsätzen und Reden der Zwanzigerjahre strampelt er in komischer Heftigkeit und unter wirklich ergreifender Anstrengungen weg von den “Betrachtungen” ; es gelingt eigentlich nicht.” Martin Walser : Ironie als höchstes Lebensmittel oder: Lebensmittel der Höchsten. In : Edition Text und Kritik Thomas Mann. Hrsg. von Heinz Ludwig Arnold, München, 1976. p. 5-25.

[17] Schröter (zie noot 2), p.95.

[18] Telkens Thomas Mann een studie schreef over literatuur en beroemde literatoren, schreef hij tegelijkertijd ook over zijn eigen kunstenaarschap. Dit is vaak als narcisme geduid, maar kan even goed teruggaan op zijn protestantse opvoeding, die hem had geleerd dat men steeds verantwoording moet afleggen en rekenschap moet geven over persoonlijke daden, keuzes en voorkeuren. Het mag in dat opzicht niet verwonderen dat hij eveneens een verwoed dagboekschrijver was. Karthaus (zie noot 6), p. 23.

[19] In 1919 had Mann reeds een eredoctoraat van de universiteit van Bonn ontvangen. De Nobelprijs was de eerste onderscheiding die wereldwijde erkenning impliceerde. Merkwaardig is dat hij de prijs voor “Die Buddenbrooks” ontving, en niet voor zijn hele oeuvre.

[20] Mann maakte een duidelijk onderscheid tussen zijn kinderen. Hij hield het meest van de oudste en artistiek erg begaafde Erika en Klaus en van de kleinere, maar heel schattige Elizabeth. Hen trok hij schandelijk voor ten opzichte van de drie andere kinderen. Aangezien Katia de praktische leiding van het huishouden op zich had genomen en Thomas vaak in zijn werkkamer zat te schrijven, had hij weinig autoriteit over zijn zes kinderen. Naar buiten hield hij het masker van de nette burger op, maar zijn gezin kende hem als kunstenaar-in-kamerjas. De kinderen Mann kregen een vrije en onburgerlijke opvoeding. Kurzke (zie noot 4), p 298-321.

[21] In tegenstelling tot zijn vader beleefde Klaus zijn homoseksualiteit openlijk.

[22] Kurzke (zie noot 4), p 315.

[23] Schröter (zie noot 2), p. 106-107.

[24] Manns tegenwoordig erg hoog aangeslagen interpretatie van het leven en werk van de Duitse componist Richard Wagner stond immers haaks op de interpretatie van de nationaal-socialisten. Vooral het feit dat Mann Wagners nationalisme historisch relativeerde, stootte hen tegen de borst. Schröter (zie noot 2), p.109.

[25] Naast de bovengenoemde hetze, was er immers ook het feit dat Katia Mann half joods was.

[26] In 1935 was hem een tweede eredoctoraat toegekend, ditmaal door Harvard University. (voor het eerste, zie noot 19) Het hoeft dus niet te verwonderen dat de zittenblijver uit Lübeck een professorenstoel veroverde in Amerika.

[27] Schröter (zie noot 2), p. 127. Kurzke verwoordt het kleurrijker : “Immer noch ist er mit dem väterlichem Pflichtbewusstsein bei der Sache, nicht mit dem frei schweifenwollenden künstlerischen Mutterherzen. Tief innen billigt er gar nicht, was er tut. Welch unsinniges Opfer, sich mit der Bekämpfung des Faschismus das Blut zu verderben!” Kurzke (zie noot 4), p. 449.

[28] Kurzke (zie noot 4), p.444-449.

[29] Daar verwijt men hem immers ‘Deutschfeindlichkeit’. Er komt kritiek op zijn houding in WO II, men rakelt zijn politieke geschriften uit de tijd van WO I weer op om hem in een des te kwalijker daglicht te kunnen stellen, men haalt zijn oeuvre naar beneden en verwijt hem communist te zijn. Schröter (zie noot 2), p. 144-146.

[30] Schröter (zie noot 2), p.142.

[31] Aan deze satire op de Belle Epoque had hij reeds in 1910-1913 geschreven. Het werk was vervolgens blijven liggen, om veertig jaar later alsnog te worden hervat.

[32] Geciteerd in Schröter (zie noot 2), p.157, eigen vertaling.